You are viewing

1 of your 3 free articles

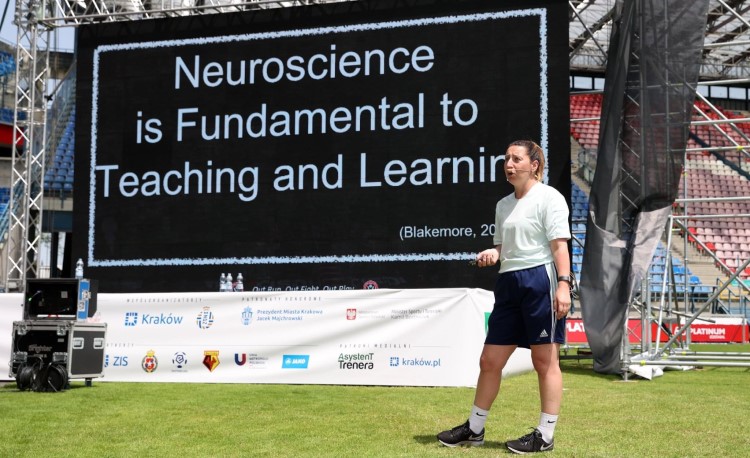

Sally Needham: How neuroscience holds the key to understanding behaviour

When it comes to understanding player behaviour, human development specialist Sally Needham says neuroscience holds the key. She explains to Carrie Dunn how to harness it and transform coaching relationships.

Every coach has players they remember throughout the rest of their careers.

For Sally Needham, one of those she struggled with the most turned out to be the one that changed her life.

“I had a player who I really get on with now, but, at the start, she was a nightmare,” she tells Women’s Soccer Coaching.

“I used to come home and nearly be crying sometimes. She would disrupt my sessions and was awful with me. It got to a point where I was starting to dislike her and thinking: ‘Do I stay, do I go?’”

Needham unloaded her stress on her best friend, who was working in a primary school with children with emotional and social needs, and the advice she got surprised her.

“She said to me, ‘You’re looking at that behaviour all wrong’.”

The insight from her friend led her to sign up for a training course with the company Thrive, based around what they call the ’Thrive approach’, an intervention designed to improve the emotional and social wellbeing of young people.

Needham learned about what happens with brain development from conception and throughout childhood, how to understand behaviours, and the role of the adult in supporting a child. It changed her entire outlook on coaching as well as her understanding of herself.

“I had a player who was a nightmare. I used to come home and nearly be crying...”

She had been coaching for many years and during her time in coach development with the Football Association had been selected as a learner for the Advanced Youth Award pilot in 2012.

“There were 60 of us - 59 males and me,” she notes, wryly.

Needham was especially interested, even then, in the elements of psychology and sociology and began to think about the ways in which coaching can encourage and support the qualities they want to see in their players.

“[The word] ’confidence’ gets bandied around,” she says. “Well, what is it? Where does it come from? Why do these sessions help that?”

Needham benefited from the support of the late Doncaster Belles coach Julie Chipchase, who welcomed her on board with the club and gave her space to try out her new learning with coaching sessions.

Since then, and with a Uefa A licence in hand, she has developed her expertise in human development and performance culture, working with Sheffield United, Cymru [Wales] Women and her own coaching company, 4Growth. She is also completing a doctorate in the subject.

Neuroscience might sound a complex and complicated term, but Needham says it’s fundamental to coaching - and something that coaches are already familiar with, even if they don’t know it yet.

“It’s basically an understanding of how your brain and your body operate together,” she says.

“Your nervous system connects into your brain and your brain connects into the nervous system. [It’s about] how that interacts and plays out.”

For Needham, understanding neuroscience is fundamental for teaching and learning.

“If a player comes into a session, or into analysis, and they’re not in what we call at Sheffield United our ‘green-zone state’, they’re not ready for learning,” she explains.

“There’s limited learning taking place. They’re not up for relationships, which we know is fundamental to team sports.”

Recognising different behaviours is important for coaches, so they can understand who is on the pitch in front of them, appreciating the individual and the experiences that have shaped them.

It is also important for coaches to understand behaviours accurately; what has previously been labelled as “challenging” is simply “distressed” - and “attention-seeking” does not exist.

“People want to feel safe, to have connection, to feel heard and seen,” says Needham, adding that these ideas around behaviour regulation, safety and connected relationships all combine in what’s known as the ‘polyvagal theory’.

“There’s a reason why they’re going to that [distressed] state - there’s a trigger with it. Understanding that and trying to have a different lens on it, instead of just reacting, is key.”

Keeping calm, Needham believes, is absolutely crucial.

“As an adult, you can’t help to regulate a dysregulated child if you are dysregulated yourself,” she said.

The language coaches use with players also needs to be considered carefully.

Needham suggests phrases such as: ‘I’ve noticed’, ‘I’m guessing’, ‘I’ve seen’, ‘I’m wondering’ - what she describes as “limbic-whispering language, that’s inquisitive around the behaviour” - in place of emotional reactions to behaviour or responses, such as: ‘You always do this’, which puts the player into a defensive state.

Coaches should, of course, be focused on what happens on the pitch during a session, but Needham advises some thinking around what happens before everyone gets there.

If, for example, children have been inside at school all day and not been able to get outside at break because the weather has been inclement, or a senior player has had a row with their partner, a coach needs to recognise that they are still in the ‘red zone’ and are not ready for learning.

Needham suggests some steps before the start of a session could help: a straightforward activity on arrival and the coach greeting each player with a warm tone, a smile and using their name.

This will get them into a more relaxed mood and reinforces the connection between coach and player.

A calm, supportive and emotionally aware coach also demonstrates useful behaviour for their players.

Related Files

“Every interaction you have is an intervention,” said Needham.

“If you are regulated and present, and you can give moments of safety, you’re helping to strengthen that player’s window of tolerance. You’re giving them emotional resilience.

“[From] a neurological perspective, if you are having that core regulation and you’re calm, you are also displaying and modelling behaviours that they will learn.

“Children really are a product of what they see and feel, and how they act, from early childhood. That’s why the formative years are so important.”

Children will grow up and take on more ownership of their self-regulation, but that will be a result of what they have received and seen from adults earlier on in their lives.

Needham added: “That’s why I’ll say to people [who are coaching], ‘Do not ever underestimate the hour, or 40 minutes, you have with that child.’ That could be the most purposeful and emotionally resilient hour that that child has.”

The best thing, Needham says, is that a lot of the elements that might be best practice from a neuroscience standpoint are already common practice in coaching - it’s just a case of acknowledging that and embedding it even further.

In her doctoral research, some of her interviewees have given her a fascinating insight into how players perceive their coaches.

“The coaches that players have felt [are] the best coaches have basically done this instinctively and intuitively,” she says, “but now we know the science behind it.”

That scientific understanding can give coaches the prompt to behave differently themselves, tweak their session plans slightly, or simply just be aware that something as straightforward as greeting a child on their level makes a huge impact on that individual.

A coach’s physical positioning can also be important. Needham says that if she sees a player tipping into dysregulation during a session, she will go and stand near them so that the physical proximity of a calm presence helps them to regulate themselves - a process called co-regulation through neuroception.

Some coaches might not initially be keen on the idea of taking time out during a session to work on these things – particularly those who have very limited time with their players or are prepping for a big match.

“I get that,” acknowledges Needham. “But you are going to get more out of the players in the sense of learning, tempo and competition and you’re giving them such a big life skill in emotional resilience.

“The quicker that gets embedded, the less time you’ll have to do on those interventions throughout a season.

“If you have those players for a couple of years - which I did in grassroots, I had a boys’ team from U13s to U16s - at 16 you become redundant, because they man-manage themselves.

“It’s a beautiful journey to view and experience.”

the ‘feel-good chemicals’ that help players to self-regulate

Lots of elements can encourage players to self-regulate during a session or a match, even when they find themselves experiencing frustration or unfairness, the two biggest threats.

High-fives in a huddle are a safe and positive way to exchange touch and also boost the nervous system. A space in which players can remove themselves from a situation and take a break to self-regulate might also be beneficial.

Checking in at the end of training and asking a player to give a thumbs-up, thumbs-down or thumb-in-the-middle to indicate their current mood could also help you gauge the impact of the session.

Sessions can replicate difficult match situations and give players the chance to break habits of behaviour.

If players had dysregulated during a match due to anger with a referee’s decisions, Needham says she might take that into training - setting up a game in which she, as the match official, makes some bad decisions to give the players the chance to respond differently.

“You can say, ‘How did you feel? A bit of breath work? Does your mate need to help you out?’” she says.

“It’s always feel-good chemicals that gets us back into regulation. Framing is really important, otherwise you’re just re-ingraining that negative experience.”

BREATHING EXERCISES, MEDITATION, JOURNALING OR JIGSAWS – SALLY’S ADVICE TO COACHES ON STAYING POSITIVE AND RELAXED

It can be tough for coaches to be in a relaxed and positive frame of mind ahead of a session, especially if they are volunteers or have had a tough day at work.

Needham recommends using the journey to the session for some breathing exercises.

“The biggest tip I could give is to do breath work daily,” she says, describing it as ‘the remote control of the body’.

“All we’re doing when we get into that ‘red zone’ is filling the body with chemicals that end up eroding the nervous system in our brain and it fractures the relationship, which doesn’t help.

“If we’ve been at work all day and we are volunteering at night, or even if we are getting paid for it, we want to enjoy it!

“How you feel, how the players feel, how that connection is – [with coaches self-regulating] the tempo will go up, the enjoyment will go up, the connection will go up.”

Needham also suggests meditation, journaling, Lego or jigsaws as other elements that could be introduced to a coach’s regular routine to improve their self-awareness and through that their ‘window of tolerance’.

“People say to me all the time, ‘You don’t get triggered much,’” she says, adding that she has worked on this.

“The more we can try and stretch that window of tolerance, the more we stay in optimal level before we then tip into dysregulation.”

Newsletter Sign Up

Newsletter Sign Up

Discover the simple way to become a more effective, more successful soccer coach

In a recent survey 89% of subscribers said Women's Soccer Coaching makes them more confident, 91% said Women's Soccer Coaching makes them a more effective coach and 93% said Women's Soccer Coaching makes them more inspired.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Women's Soccer Coaching offers proven and easy to use soccer drills, coaching sessions, practice plans, small-sided games, warm-ups, training tips and advice.

We've been at the cutting edge of soccer coaching since we launched Soccer Coach Weekly in 2007, creating resources for the grassroots youth coach, following best practice from around the world and insights from the professional game.

![Sally Needham is a Uefa A licensed coach, who has worked for Sheffield United, Cymru [Wales] Women and her own coaching company, 4Growth Sally Needham is a Uefa A licensed coach, who has worked for Sheffield United, Cymru [Wales] Women and her own coaching company, 4Growth](https://d3rqy6w6tyyf68.cloudfront.net/AcuCustom/Sitename/DAM/138/wsc-038-the-brain-game-1.jpg)